As heatwaves grow more severe, they are having severe impacts in terms of mortality, disruption of daily life, and deepening inequalities.

Unlike other climate-related disasters such as hurricanes or floods, extreme heat is an invisible crisis that intersects with multiple areas like urban planning, transportation, public health, and energy systems. Thus, traditional institutional response mechanisms struggle to address the chronic and systemic risks posed by extreme heat.

To fill this governance gap, many cities have recently created new teams and roles dedicated to heat resilience, such as the role of Chief Heat Officers (CHOs) in cities including Athens, Freetown (Sierra Leone), Dhaka (Bangladesh), and Los Angeles.

CHOs work across sectors, collaborating with urban planners, public health officials, and community leaders to implement heat mitigation measures such as:

- Expanding tree canopies

- Increasing access to cooling centres

- Designing heat-resistant infrastructure [1]

They also lead public awareness campaigns, ensuring that heat risks and solutions are communicated effectively to vulnerable populations.

We expect roles like this to become increasingly normal over the next few decades as global temperatures continue to rise. Ahmedabad in north-western India is a good example, which we look at in more detail.

Heat is an invisible killer and is increasingly disrupting daily life around the world.

Between 2000–2019, studies show approximately 489,000 heat-related deaths occurred each year, with 45% of these in Asia and 36% in Europe (WHO, 2024). Tackling heat is challenging because it has many cross-cutting impacts, affecting healthcare, infrastructure, labour productivity, and social well-being.

However, the traditional siloed structure of institutions, budgets, and policies means that it’s often difficult to address the challenge of heat systematically.

For example:

- Healthcare systems may issue heat advisories but rarely coordinate with city planners to redesign neighbourhoods for better airflow or shade.

- Labour regulations can lag behind in protecting outdoor workers, particularly in construction or agriculture, where high temperatures pose serious health and productivity risks.

This fragmented approach, with separate budgets and narrow mandates, prevents comprehensive strategies that could reduce urban heat islands, improve infrastructure resilience, and safeguard vulnerable populations.

For these circumstances, the increasing frequency of heat waves has pushed many countries and cities to rethink traditional approaches and establish new roles and institutions to tackle the threat of extreme heat.

Ahmedabad’s response

India has been particularly vulnerable to extreme weather events, including heatwaves. Between 1992 and 2015, heatwaves alone caused over 24,000 fatalities.

In May 2010, Ahmedabad, a city in northwestern India, experienced one of the deadliest heatwaves, resulting in over 1,300 excess deaths in just one month. Vulnerable groups, including daily wage labourers, elderly residents, children, and slum dwellers, were most affected. There was no structured approach to responding to the effects of heat waves. The response was largely reactive, with limited public awareness or coordinated efforts between government departments.

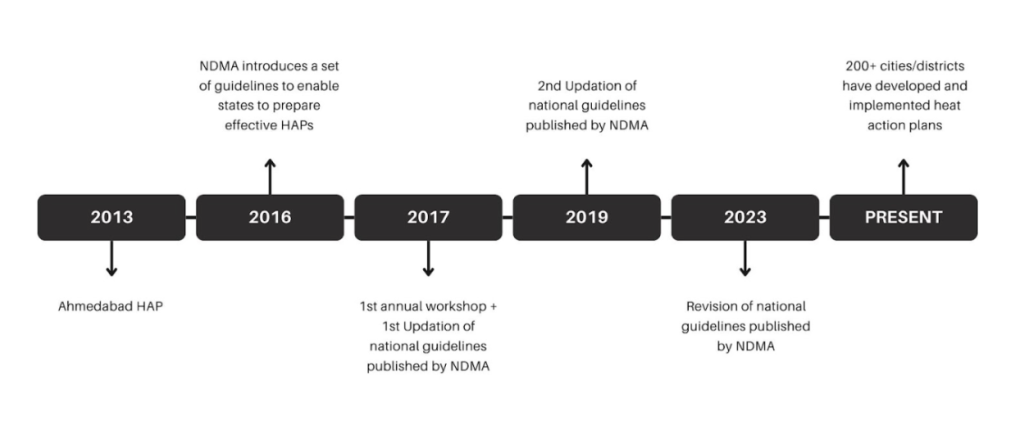

The crisis prompted Amdavad Municipal Corporation (AMC) to collaborate with scientists from NRDC, the Indian Institute of Public Health (IIPH), and the India Meteorological Department (IMD) to develop India’s first heat action plan specifically tailored for a municipality in 2013.

The plan included four key strategies:

- Building Public Awareness and Community Outreach,

- Establishing an Early Warning System and Inter-Agency Coordination Mechanism

- Capacity Building of Health Care Professionals and

- Reducing Heat Exposure and Promoting Adaptive Measures

These targeted interventions have significantly improved the city’s ability to manage heatwave risks. Epidemiologists estimate that HAP has helped avert more than 1,000 deaths annually:

“The Ahmedabad Heat Action Plan is a necessary step towards protecting our communities from extreme heat and a beautiful model for future climate adaptation efforts.” – D. Thara, Ahmedabad Municipal Commissioner

The Ahmedabad HAP is a work in progress, with stakeholders regularly revising it based on feedback and emerging challenges.

For example, the plan was updated in 2016 to incorporate new strategies and lessons learned from previous years. Further revisions were made in the 2018 plan, which introduced measures like expanding the use of cool roofs, increasing access to drinking water, and enhancing public awareness campaigns.

A local solution that saved lives

The success of this action plan set a precedent for broader national efforts.

UDrawing lessons from the Ahmedabad HAP, the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) released comprehensive guidelines – emphasising early warning systems, public awareness, capacity building and inter-agency coordination.

The guidelines allowed for flexibility and experimentation as states and cities were encouraged to develop Heat Action Plans in local contexts. This initiative served as a catalyst, gradually building local institutional capacity and laying the foundation for long-term resilience.

Over 200 cities/districts in 23 heatwave-prone states have now developed localized HAPs, creating a robust framework for addressing extreme heat.

These are developed through collaborative efforts between government agencies and non-governmental organisations.

For example, Surat’s plan was supported by the Resilience Strata Research and Action Forum, Gorakhpur’s by UNICEF and the Uttar Pradesh government, and Thane’s by the Council on Energy, Environment, and Water (CEEW).

“India is showing the world that, as we work together to fight climate change, we can take smart steps right now to shield millions of people from killer heat waves. These groundbreaking heat action plans also demonstrate that it’s clearly feasible and cost-effective to create similar heat preparedness plans across Indian cities and states” (Reference) – Anjali Jaiswal, the India Initiative Director at NRDC

The impact of these efforts has been significant. Heatwave-related mortality has declined dramatically, from 2,040 deaths in 2015 to just 4 in 2020.

India’s response to heatwaves shows how governments can tackle cross-cutting challenges that don’t fit neatly into existing institutional structures. The Ahmedabad Heat Action Plan, which began as a local response to a deadly heatwave, shows how resilience can be improved when institutions rethink traditional boundaries and embrace interconnected approaches.

Addressing extreme heat catalyzed a shift in India’s disaster management approach, opening doors to rethink solutions in domains like health, poverty, and education.

At UNDP Istanbul Innovation Days

How can public institutions evolve to tackle transversal challenges like heat, care, and time—issues of that cut across silos?

If we had to invent a new city from scratch, how would it manage heat?

At IID, we invite all participants, innovators, experts, decision-makers and practitioners to explore how institutions can become more resilient and proactive in the face of the interconnected challenges of our time.

Much like the emerging institutional responses to extreme heat, we will, through plenaries, discussions, and workshops, provide inspiration to look for alternatives and work to identify pathways for reimagining institutions that build societies capable of thriving in an uncertain future.

This case was researched as part of Istanbul Innovation Days 2025, the UNDP’s flagship event on public innovation, and first shared on the event’s official website. We are thankful to our colleagues at UNDP and Demos Helsinki whose contributions were essential for this case story to be told.