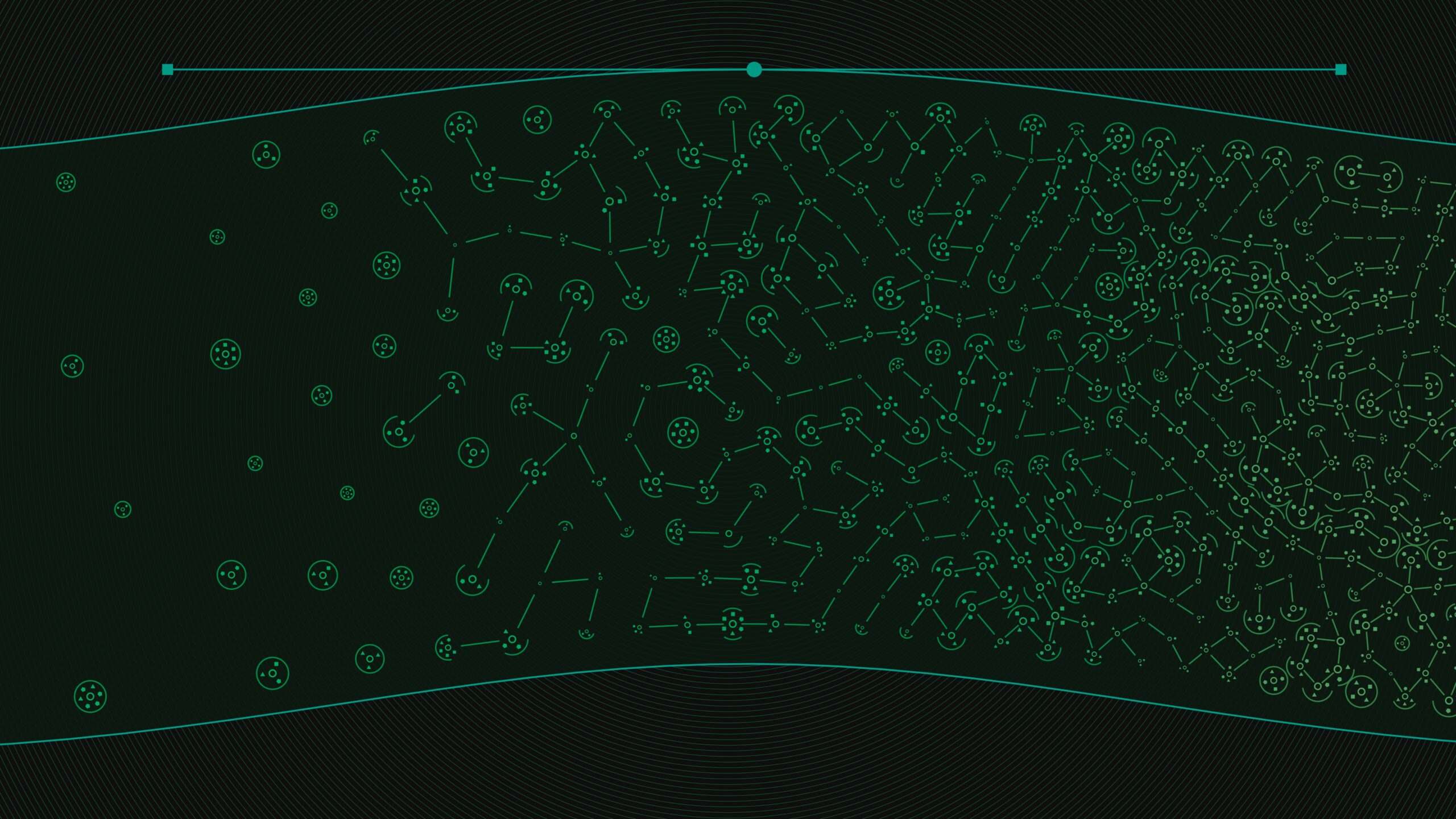

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed a striking lack of global data coordination among public institutions. While national governments and the World Health Organization struggled to collect and share timely information, a small team at Johns Hopkins University built a public dashboard that became the world’s most trusted source of COVID-19 data. Their work showed that planetary-scale data infrastructure can emerge quickly when practitioners act, even without formal authority. It also exposed a deeper truth: we cannot build global coordination on data without shared standards, yet it is unclear who gets to define what those standards might be.

This paper examines how the World Wide Web has created the conditions for useful data standards to emerge in the absence of any clear authority. It begins from the premise that standards are not just technical artefacts but the “connective tissue” that enables collaboration across institutions. They extend language itself, allowing people and systems to describe the world in compatible terms. Using the history of the web, the paper traces how small, loosely organised groups have repeatedly developed standards that now underpin global information exchange.

Four examples illustrate this pattern:

- RSS (Really Simple Syndication) allowed information to flow across websites and became the backbone of today’s content distribution systems.

- Markdown simplified web publishing by turning plain text into structured documents.

- GTFS (General Transit Feed Specification) provided a common format for transit data that allowed agencies around the world to reach riders through applications like Google Maps.

- STAC (SpatioTemporal Asset Catalogs) did the same for satellite imagery, creating a shared structure for vast Earth observation datasets.

Each arose from practitioners solving specific problems. They succeeded because they were open, simple, and immediately useful.

From these cases, several principles emerge:

- Successful standards evolve from small, functioning systems rather than grand designs. They remain lightweight and adaptable. Their creators are practitioners who understand real constraints.

- Once these standards prove useful, their adoption by credible institutions transforms them into durable infrastructure. RSS gained momentum when the New York Times adopted it; GTFS scaled globally once Google Maps embraced it; STAC became a fixture of Earth data management when NASA and Microsoft implemented it.

- Institutions seeking to coordinate around shared data – whether in health, climate, or other global challenges – should learn from these examples. Instead of designing top-down systems, they should create conditions in which small groups can build minimal, working standards that others can adopt. This involves funding collaborative sprints, supporting open formats, and adopting procurement policies that favour interoperability over proprietary control.